If we think of art as something to be viewed and admired, we may be perplexed by Rirkrit Tiravanija’s work. Transporting everyday prosaic affairs into other odd settings, Tiravanija is an artist whose work builds a new set of relationship and creates unexpected participation. Creating situation-related spaces for communication and interaction, his famous ‘installations’ include setting up sizzling food stalls, reconstructing his apartment, setting up a meeting place – all within the spaces of art museums. As we enter these galleries, we become participatory constituents of the work itself – even if we never intended to interact – and become almost delirious as to the question of where, when and how because the situations are at once both strange and familiar. Tiravanija’s house is equally puzzling.

Being in Chiang Mai, the northern province of Thailand, means the house is located in a place known for its strong historical, cultural and architectural heritage. Designed by Aroon Puritat in association with Fernlund + Logan Architects, the house seems at odds with any architectural preconceptions one may have about the place.

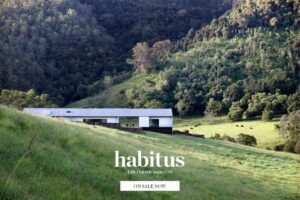

Upon arrival, not only does the obscurity of the entry represent both a defeat of authorship and ownership, but from outside, little if anything of the settings within is disclosed through the passage. Along this passage, we are drawn to the marks cast into the surface of unpolished concrete panels, which in turn, form the shape of both the house’s interior and exterior spaces. Simple geometric shapes of concrete and glass give the house a mute or rather quiet expression, receding into the lush trees hovering above it.

The first and foremost requirement was to keep the existing trees in place. Thus they act as a pretext to the design: they give the framework of both the interior and exterior spaces. Along the design process, the roles of owner and architect gradually merged. Creative inputs and active dialogues from both sides allow the design to transform into something neither deliberately ‘owned’ nor ‘designed’. It would be a place that accepted and welcomed both prosaic and aesthetic transformation.

Organised around a central courtyard, activities are simply divided into two groups of ‘private’ and ‘public’ activity. Yet there is never a clear line between them as the court allows both parts to participate in any daily activities that may occur. This is not much different from Tiravanija’s work. His art and his house can be seen as a transformation of place, merging different activities into a unified whole. The ‘public’ space of the house integrates four distinct settings into one ensemble: the kitchen or cooking area, the space for dining, the living room and the studio. Each is defined by its own equipment. The extended porches enveloping the spaces simply bind together settings for cooking, eating, living and working.

The climate – which encourages people to spend time out of doors – has brought forth the design, with its courtyards, verandahs and porches enclosed with glass panels. This makes it possible for inhabitants to live both inside and outside the house, and also in the in-between areas. Shadows produced by the brim of a solid slab allow for rest and for all the other daily domestic activities to unfold protected from the sun.

In so far as the Thais are still the same people and the climate has not changed, these types are still valid, no matter how traditional or ‘modern’ the house may appear. By means of open-air covered spaces, interior and exterior can be bound together.

In Tiravanija’s installation, art and the viewers can be seen as a network of relationships. This same notion of participation allows the connection between interiority and exteriority, as well as the transition between distinct activities. The connection is both spatial and actual. The extended terraces around the ‘interior’ space are the means by which the vision can be led beyond the walls and the house can sustain the sense of free flow. Yet, the physical connection between inside and outside is always a choice – never was there an opening without closable doors and windows. It is only that the presence of them is never apparent. Once opened, they seem to disappear. Thus the hints of threshold are given, but the actual separations are delayed.

As for the outward appearance of the house, it is simply formless, as if being shaped and re-shaped by specific circumstances and situations. We never feel that the house is being ‘designed’ to have its own distinct identity. Rather, it is being built as a framework or background to daily life and it is the presence which contrasts to the architectural heritage of the place. It is formlessly quiet. And because it contains specific activities whose relationship is transformative, had the house been different from the architectural culture in which it sat, it could not have been re-joined to both the place and the inhabitants so closely. In this case, the building, the place and the activities can be joined only if they are distinct, interlocked only if separate. For only when they are different can they perform their roles respectively and only then can the energy of daily activities animate the house.

As with Tiravanija’s installations, the task of describing the place becomes clearer: it is to develop vocabularies and concepts that will demonstrate how settings that are distant and distinct from one another can also interconnected, how they can remain apart and be joined. To inhabit the house means to focus on the performances that the separate settings sustain, and to discover similarities between them. Only in this way will architectural setting be seen to exhibit not just remoteness, but familiarity – that is, the typicality of recurring situations in a different place.

Thinking of the specific situations of daily life as well as its possible adjustability allows one to witness more clearly the play of its different forms of articulation. In this case, both the architect and the owner have created the possibility of participation and transformation. The presence of the historical context is never obtrusive. On the contrary, it remains as a faint trace that allows current situations to perform. In this house, material, spatial and participatory quality is not an accomplishment, but a task: for both tradition and the current situation to stay alive, they must be re-made. Thus, both the owner and the architect allow the house to withdraw from an object-like situation in order to transcend itself into the conditions of its own becoming.

ARCHITECT

Aroon Puritat Architect

DESIGN DEVELOPMENT ARCHITECT

Fernlund + Logan Architects

fernlundlogan.com

LIGHTING DESIGN CONSULTANT

Thaneeya Yuktadatta

CONTRACTOR

Settawut Pinyorid

ARTISANS

Ai Deang, Somkid, Ai Teaud, Uncle Neua, P Bann, P. Aod

Photography by Jason Schmidt, Pirak Anurakyawachon